No Such Street in Haifa

Umberto Eco writes in his book, A Theory of Semiotics: “Semiotics is concerned with everything that can be taken as a sign. A sign is everything which can be taken as significantly substituting for something else. This something else does not necessarily have to exist or to actually be somewhere at the moment in which a sign stands in for it. Thus, semiotics is in principle the discipline studying everything which can be used in order to lie.”

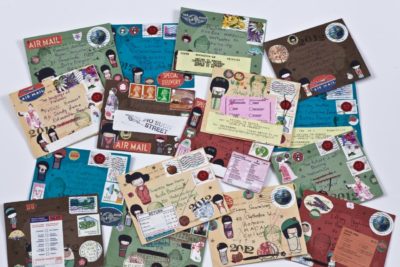

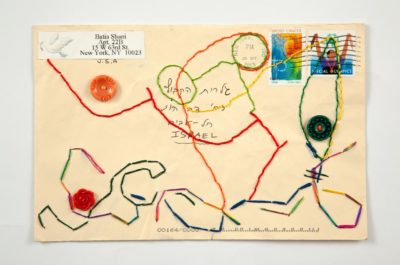

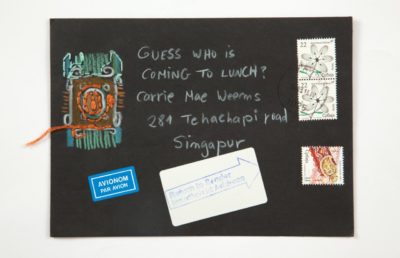

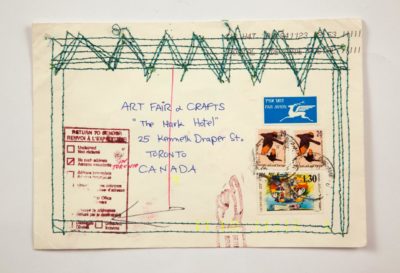

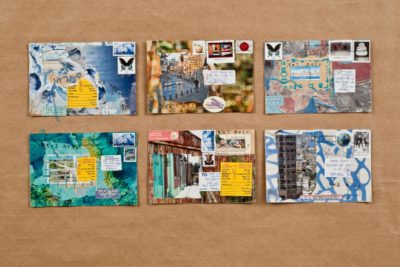

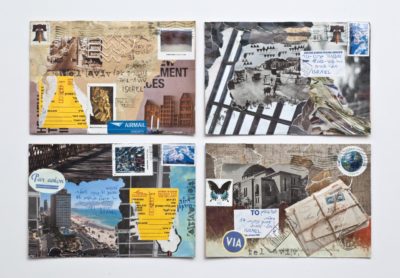

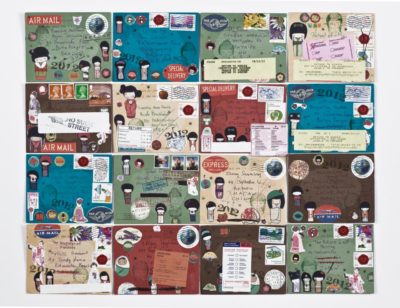

The surface of the envelopes Batia Shani has been sending to fictitious, non-existent addresses is covered with a rich system of signs, comprising postal stamps, words, drawings, embroidery, and collage. Sometimes, but not always, the text and the image match. Other signs are added on, imprinted by postal services throughout the world, referring to the unknown recipient and to the fictitious address, which has not been found. On first encounter with the envelopes the viewer is amazed by their richness and physical beauty, but soon an embarrassment sets in, a lack of understanding resulting from the attempt to decipher the addresses and the weird, funny, nonsensical, enigmatic names, and to find out what’s behind this artistic course of action.

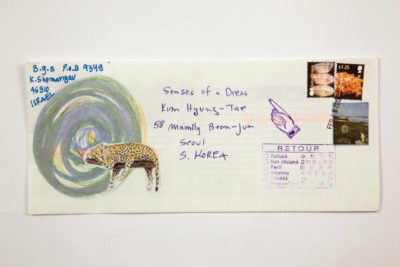

The first set of envelopes was sent in 1994, as an act of trial and error. Shani sent out envelopes, decorated with embroidery, to galleries and various art institutions, naively expecting to get them back with some added element or with a letter. Most envelopes were not returned. Bypassing the art world in an act intended to avoid imminent disappointment, and suggesting a different form of display, she continued sending envelopes around the world. This time she tried to control the process and make sure that most of them would be returned. As one who had an unrebellious childhood, she now decided to be a “bad girl,” to be naughty, to have fun, and to fool postal services worldwide. Shani began sending envelopes from places around the globe, where she had stayed, to non-existent people in fictitious addresses, knowing that the envelopes would be returned when the address or the person would not be found. The return address was her own residence at the time; the envelopes were mailed in one country, addressed to another, and then returned to her home at the end of the process. Her manipulation of the postal services made the postal workers in different countries active participants in the envelope project. With their help, but without their knowledge or permission, she has created a wide-ranging, border-crossing exhibition.

In the foreword to his book Art Power, Boris Groys2 writes: “The dominating art discourse identifies art with the art market and remains blind to any art that is produced and distributed by any mechanism other than the market”. The way in which Shani has chosen to distribute her envelopes was no doubt an act of protest and defiance against the art world, with its rules of acceptance and its exclusion of “outsiders” like her, who did not match the archetype of the certified artist, as perceived by the active players in the art market.

The switch from the playful, humorous, free act of sending the envelopes to making them a pointedly political statement occurred after the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1995. Shani has decided to commemorate the first anniversary of his death by mailing envelopes with a postage stamp carrying his portrait. The decision stemmed from her wish to share the tragedy with people around the world and to expose them to the rift experienced by Israeli society. Years later she employed a similar tactic with envelopes carrying stickers which read “Free Ron Arad” and “Gilad Shalit is Still Alive.” Having chosen to work with subject matter borrowed from real life in a conflict-ridden country, she considered humor and playfulness no longer legitimate, and in those few cases she has opted for real addresses. Those tragedies and the collective trauma connected in her mind to her encounters with bereaved families as a social worker, as well as with a personal sense of loss as the daughter of Holocaust survivors. Having grown up in a home with no visual memento of the past, she used the envelopes to create an archive of memories for her children and grandchildren. The use of the envelopes, which are meant to contain letters, an almost extinct form of communication in our digital era, is in itself an attempt to preserve something of the old world for future generations.

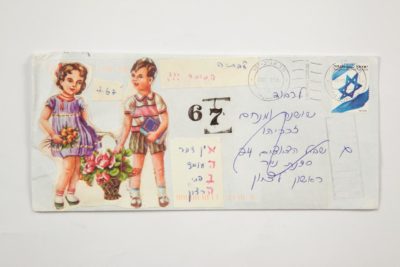

Shani’s process is nostalgic, but the industrious, obsessive action, stemming from an uncontrollable impulse, has never made room for thinking or for sorting, pushing consciousness aside. An examination of the envelopes reveals that stamps containing the number 48, 67, and 73 appear in several series. Shani has stamped on the envelopes three dates, highly significant in Israel’s history and in its narrative of three wars, whose courses and consequences affect life in Israel to this very day. These wars, whose ghosts still haunt individual Israelis and the society as a whole, are largely responsible for shaping Israeli society and for many of its maladies, first and foremost the occupation of the Palestinians. Shani herself has served in the Yom Kippur War and many of her cohorts were injured or killed in this war. The numbers appear next to the Hebrew word for “dress” or to a painted image of a dress. The Hebrew word for “war” is feminine, but its connotations evoke masculinity, aggressiveness, violence and destruction, while the dress (also feminine in Hebrew) relates to femininity, softness, and seduction. The encounter between masculine and feminine is a major issue in Shani’s art. Exploration of femininity, sexuality, traditionally feminine crafts, and her own identity as an artist in the context of a family, of being a wife and a mother, occupies a central place in her work.

Shani’s own biography, which includes wandering and living in different countries while contact was maintained mainly by letters, no doubt carried weight in her decision to work with envelopes. Despite her many years of art-making, the travelling, and the exposure to international art, Shani has been unaware of the Mail Art movement, which begun with the Fluxus movement in the 50s and 60s, with Ray Johnson as its herald. While early mail artists based their work on conceptual issues and on connecting with other artists, and placed less value on aesthetics, Shani’s has focused on just the opposite. The action is reflexive, the dialog is with herself, and the visual dimension is highly important. The containing aspect of the envelope has been disposed of and its surface is used as a bed for collage. The surface also signifies a point of encounter and friction between the individual and the state, between the writing, speech, and the memories of a private person and the authorities in various countries who scan this private information, voiding and deleting it when it does not conform to the system’s logic.

In his project Dossier Postale (1969-70)the Italian artist Alighiero Boetti sent 26 envelopes to well-known artists, curators, art dealers, and critics. The people were real, but the addresses were erroneous and they were all returned to the sender. The idea behind sending the envelopes was to explore issues of randomness and improbability. Between the years 1968-1979, the Japanese artist On Kawara sent his gallerist and acquaintances a series of postcards called I got Up At, from different places and different time zones around the world. The postcards stated the time in which he woke up, as part of his interest in and exploration of the dimension of time.

Shani’s envelopes are mailed, but there’s no knowing when, and if, they will come back. Their journey occurs in an alternate dimension to ordinary, regular, daily time – it is not pre-ordained, and despite the wish and the attempt to control it, it remains ungovernable.

Over the years Shani’s envelopes have been recognizable by their handicraft – painting and embroidery. In the recent series, mailed in 2013, the handicraft has almost disappeared, replaced by magazine clippings with various images and only the addresses are written by hand. The importance and focus changed, from making an image to selecting an existing one. The release from the tyranny of the original image, which for Shani has been a guileless process, turned out again to be in sync with the spirit of the time. In this era of an endless flood of images, when we have at our disposal unlimited accumulations of visual information, many artists see no need to make their own original images and to add to the mass; instead they choose to appropriate existing images from the available sources.

Tamar Dresdner

References:

- Umberto Eco, A Theory of Semiotics, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1976, p.7

- Boris Groys, Art Power, the MIT Press (February 8, 2013), introduction.